Can we solve the 'truck driver problem'?

The solution lies not in technology, higher wages, or more home time, but in ourselves.

Welcome to the second edition of The Fifth Wheel with Bill Cassidy, a weekly look at a particular aspect of trucking and transportation that’s on my mind or in the news or just caught my eye. Something of a reporter’s notebook. I’ll also post occasional insights and reflections on transportation history.

The extent, nature, and even existence of the truck driver shortage is one of the thorniest issues bedeviling US shippers, freight brokers, and motor carriers today, as it has been for more than a century. The first reference to the “motor truck driver problem” I’ve been able to find dates all the way back to 1914, when there weren't enough teamsters (of horses) trained to work motorized equipment.

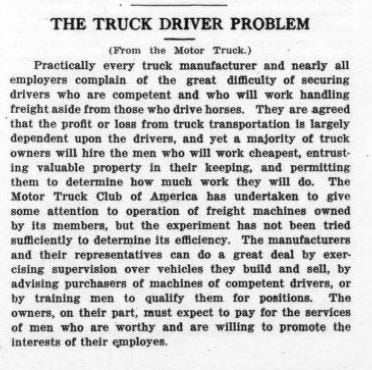

I kid you not. Here’s the article from the Dec. 12, 1914, edition of The Traffic World, page 1101:

Hits home, doesn’t it? Especially the parts about employers hiring “the men who will work the cheapest,” and the need “to pay for the services of men who are worthy.”

There’s no question that at this moment there aren’t enough truck drivers available to haul all the freight that needs to be moved. That’s especially true in the long-haul truckload sector, but it’s true for less-than-truckload (LTL) and parcel carriers too.

According to data released this month by the US Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), the number of for-hire truck transportation employees in June -- approximately 1,501,600 payroll workers, mostly but not all drivers -- was about 3.2 percent below the July 2019 pre-pandemic peak of 1,553,100 employees.

Now let’s look at volume. The Cass Freight Shipments Index was 5.1 percent higher in June 2021 than it was in July 2019, a sign of how much more truck and rail freight is in motion today than in that peak truck employment month two years ago — with 49,700 fewer drivers to haul it. And we’re still 1.3 percent short of the Cass volume level in June 2018.)

Driver counts are imperfect though. The BLS data doesn’t include sole proprietorships, including owner-operators. It only includes for-hire companies, whether local, truckload, less-than-truckload, or specialized carriers. And thousands of new small carriers are being granted operating authority each month. There may well be more drivers out there than we think, just not where shippers want them.

Can we ever solve this seemingly incurable problem? I’m an optimist, so I’d like to say yes, but I doubt hiring alone will do it. Where will the 110,000 truck drivers the American Trucking Associations (ATA) says we must hire each year over the next 10 years come from, even if we lower the minimum age of a US truck driver from 21 to 18?

Technology eventually may help us more completely understand and optimize how we deploy the drivers we do have across the trucking landscape. As we develop larger, broader, more interconnected digital freight marketplaces powered by artificial intelligence, we’ll be better able to manage our existing drivers and equipment.

But I believe the solution lies not in technology, but in ourselves. The real problem is the way we think about and “utilize” truck drivers — a term I dislike intensely. Frankly, the model used now for the job is as antiquated as the horse wagon. And if we simply apply technology simply to shore up our current processes or practices, are we really solving the problem, or placing a band-aid over the wound?

If we’re intent on offering truck drivers the same job we did in 1990, 2000, or 2010, we’re not making progress. Rather than hiring drivers to work for trucking companies, trucking companies (and their shipper customers) will have to work harder for their drivers. Smart carriers are trying to create new career paths for their drivers, giving them diverse opportunities and a greater say in the business.

“What might a really effective employee engagement program focusing on truck drivers as the most important component of the company really do? How might it shake up the industry?” Jeff Tucker, CEO of freight broker Tucker Company Worldwide, recently asked me. It’s a question we should try to answer.

And that “we” includes shippers. If they want capacity, at an affordable price, they have a responsibility here. Unless, that is, they want to continually shell out more money for higher driver pay. “I think many shippers still think the capacity issue is a carrier issue,” said Ed Burns, president of independent sales agency Burns Logistics. “There’s a lot of room for improvement in what shippers can do.”

Here are some recent stories on the topic from myself and my colleagues at JOC.com:

Record number of new US trucking firms on the books, but not new capacity (July 14, 2021)

June’s hiring gain in trucking the best in seven years: BLS (July 2, 2021)

US trucking firms add jobs, but not enough of them (June 4, 2021)

I’ll have more to say on this topic, among others, in future weeks. Thanks for subscribing to this newsletter. For those that don’t know me, I’ve been the senior editor for trucking and domestic transportation at The Journal of Commerce and JOC.com since 2009. Before that, I spent 13 years as managing and executive editor at Traffic World, a weekly magazine once owned by the JOC.

I can be reached at bill.cassidy@ihsmarkit.com, on Twitter at @willbcassidy, and on LinkedIn.